Coming to an end last weekend after a triumphant return to Sheffield's cinemas - whilst also running a virtual version for those unable or hesitant to travel - this year's Sheffield International Documentary Festival managed to offer its usual mix of film and arts, via shorts, features, Q&A's and films that pushed the boundaries of what documentary filmmakers can achieve. With 78 features and 88 shorts in the film programme it's literally impossible to watch everything available, but here's my highlights from the line-up.

Separated into the Rebellions, Rhyme and Rhythm, Into the World & Ghosts and Apparitions strands that come together in the International & UK Competitions, DocFest re-stated its identity and unrivalled Sheffield-iness (an absolute must in the era of online festivals) by including a Northern Focus strand with new and old documentaries showing life outside of 'that there London'. Opening the festival with Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson's Summer of Soul - with satellite screenings across the country - and closing with DocFest royalty Mark Cousins' latest film, Story of Looking, there were a number of other feature length docs that caught my eye.

Top of my list of must watches was Nira Burstein's much hyped Charm Circle, by far one of the most talked about and well received at the festival, and a worthy winner of the Audience Award. Focussing on Burstein's family and their life on the quiet street in Olympia, Washington that gives the film its name, we meet her mother and father as they face their ongoing mental health issues, something that has caused their home and wellbeing to fall into disarray. In many respects a 21st century equivalent to Grey Gardens' Little & Big Edie, mother Raya and father Uri could endearingly be called eccentrics at first glance, but through Burstein's eye and the use of old home video we see the toll that Raya's illness and daughter Judy's subsequent need for care has taken on the family, most notably and vocally by the stubborn and volatile Uri, who works through his own problems by writing and performing a number of bluesy tracks that are peppered throughout the film. An old rocker who crashed out of the real estate rat race years ago, he's a man at odds with the modern world, unable to comprehend daughter Adina's decision to marry into a polyamorous relationship with two non-binary people, something he sees as going against Jewish law.

As a portrait of a family who've struggled to adapt to the many challenges they've faced, it's full of charming comedic moments (Uri enters the film complaining about the crappiness of the makeshift belt he's crudely fashioned out of a plastic bag to keep his shorts up) and heart-achingly sweet snapshots as Uri realises he's in the wrong and tries to make up for it. Burstein's camera follows the Maysles' direct cinema approach at first, but in what is obviously a raw, personal film to make, she steps from behind the camera (and in the home video footage) to interact, not just document, her siblings. It's here that the film transcends into something more special, removing that disassociation her camera gives her, and us, and pulls us into this incredibly moving, relatable picture of family life. A must see.

In No Straight Lines: The Rise of Queer Comics, we're given a guided history of gay representation in comics (both in the industry and on the page) by a group of the biggest names around. The most recognisable name for a lay person such as myself - or anyone who's dipped their toe into film Twitter in the last decade - is Alison Bechdel, accidental creator of the Bechdel Test grade for female representation in film based on a 1985 strip from her 'Dykes to Watch Out For' series. Thankfully that's not the focus of No Straight Lines (in fact, I don't think it even gets a mention), and instead we're given a funny, informative history of queer comics, from Mary Wings's "Come Out Comix" of the 1970s and Howard Cruse's Wendel series taking on the restrictive nature of the "Comics Code" (a McCarthy-ist set of regulations that forbade the depiction of homosexuality) that saw their work sold in head shops and under the counter.

If you're unfamiliar with any of the key titles or artists featured, this stands as a great introduction to their work. It's impossible to deny the skill in the artistry displayed here, not to mention the personal nature of the writing that spoke to the next generation of writers and artists, many of whom who appear in talking heads to tell of their own stories and influences. As Cruse states in the film, "people should be able to do art about their lives", and you'll leave No Straight Lines feeling enlightened and hopeful for the future of the medium of comics.

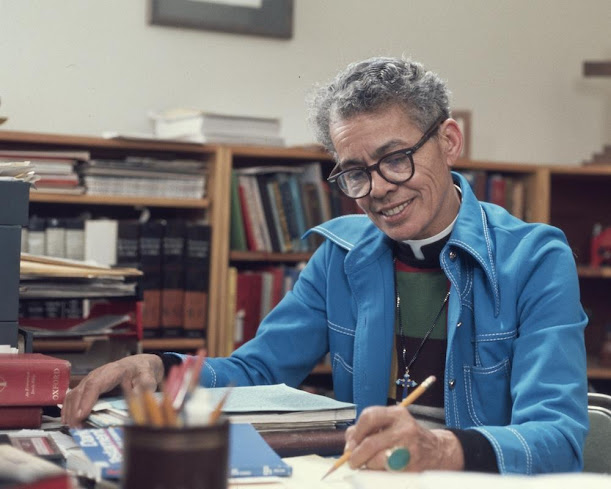

Sheffield DocFest has long been able to educate as well as entertain, one of the clearest examples being My Name is Pauli Murray, that I went into knowing nothing about the central subject but that immediately gave me that feeling of "why have I never seen a documentary about this person before?". So incredible is their story, if it wasn't for the clear, documented evidence that it happened, you'd assume it was a work of pure fiction. A black, queer, what would now most likely be thought of as non-binary person, who was a lawyer and teacher, continually at the forefront of historic social change and went on to become an episcopal priest in their final years, Pauli Murray lead an incredible life that until now hasn't been given the spotlight it warrants.

Directed by RBG filmmakers Julie Cohen and Betsy West (and including an interview with Ruth Bader Ginsberg herself among the many voices keen to tell of how important Murray's work was to them), My Name is Pauli Murray follows a similar biographical structure to their previous film, but with the added angle that Murray's life saw them arrive at various points in history, just before real change was about to be made. This is expressed to us via on screen text that hammers home the unjust world Murray lived in and how important the groundwork they laid was on shaping the civil rights and social justice advancements of the 20th century. With a stand-out subject that's incredibly timely and relevant to today's world, My Name is Pauli Murray is a statement of how much impact one person can have on the world, and should help see their work reach a whole new generation.

Now, if you'd have told me one of my favourite docs of the festival this year would be fronted by the former lead singer of Chumbawamba, I'd certainly have been surprised. Sure, I bought their anthemic single Tubthumping back in the late 90s (and still own a copy), but would a documentary about the rise and fall of the self-proclaimed anarchist pop stars really offer that much? As it turns out, yes, as I Get Knocked Down was a rip roaring ride through life on the outskirts of stardom, with that brief moment before the millennium where this little band from Leeds exploded onto the world stage and could lay claim to have the biggest song in the world.

More than just a bio-doc of the band, I Get Knocked Down follows frontman Dunstan Bruce (co-directing with Sophie Robinson) as he reckons with his role in taking the group - temporarily - into the mainstream by signing with major record label EMI and aiming for chart success, well away from their anarcho-punk roots that had served the band for the previous 15 years. Bruce does this by visiting his former bandmates (including Danbert Nobacon who infamously became front page news by dumping a bucket of ice over MP John Prescott's head at the 1998 Brit Awards, leading to his parents getting the amazing hate mail "I hope Burnley get relegated"), filmmaker Ken Loach and his former record exec in New York, all while being pelted by hurtful comments by his inner demon, depicted as a big toothed, bald-headed baby who stalks his every move. DocFest can always be relied upon to offer a great new music doc, and I Get Knocked Down is this year's hidden gem. Madcap, witty and formally inventive - what else would you expect from the frontman of Chumbawamba?

Elsewhere on the music doc front was Lydia Lunch - The War is Never Over, charting the career of the no wave singer and frontwoman for bands like Teenage Jesus & The Jerks, Shotgun Wedding and Retrovirus. If you're not familiar with Lunch this doc covers all the bases, from her riotous on stage performances to controversy baiting films made with Richard Kern that saw her strip nude and perform real sex acts as a backdrop to her powerful spoken word poetry. Labelled misogynistic at the time, it's hard to dispute that Lunch's self-expression wasn't informed by the hyper-sexualised persona she created. In her eyes, she was the exploiter.

Most of the film is - the still touring - Lydia showing she's not lost any of her edge, as she playfully flirts with men in her audience (and her band); but despite her impactful raspy vocals and extraordinary skill with a monologue, Beth B's film feels like it only captures a performance and never a true representation of the woman behind the act. It may be that Lunch has spent so long in character that the lines are forever blurred, but it's left her film feeling promotional rather than personal.

Top of the list of boundary pushing docs at this year's festival, Yael Bartana's Two Minutes to Midnight is a clash of performance and reality as several high ranking experts (and five actors), all women, gather in a recreation of Dr. Strangelove's War Room to debate the threat of nuclear war and the prospect of retaliation. Now dubbed the Peace Room, the female panel analyse the notion that having women in charge would lead to peace between nations, all while their President is conversing via telephone with the new Leader of the Free World - a Trump-esque lunatic called Arnold Twittler who's taken his finger of the 'send tweet' button long enough to hover it over the red button instead.